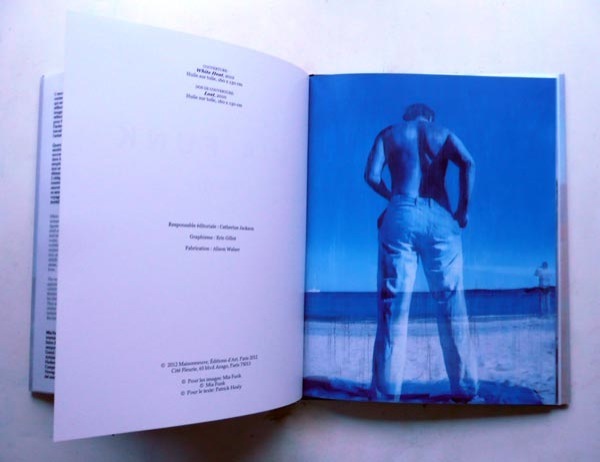

MIA FUNK

BOOKS

80 PAGES

Maisonneuve - Éditions d’Art

Hardcover book

Essays by Patrick Healy,

with additional writing by Harriet Alida Lye, Marie Juliette Verga and Lord Alfred Tennyson

Illustrated survey encompassing entire oeuvre.

Language:

English / French

33 x 28 cm

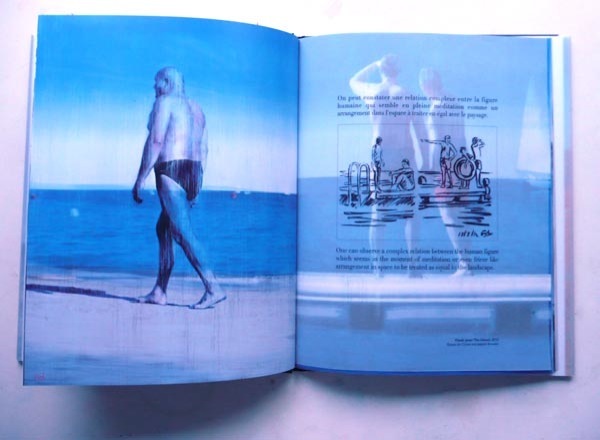

45 PAGES

Maisonneuve - Éditions d’Art

Hardcover book

Essay by Patrick Healy,

with additional writing by

Harriet Alida Lye.

Selected text by

Samantha de Bendern,

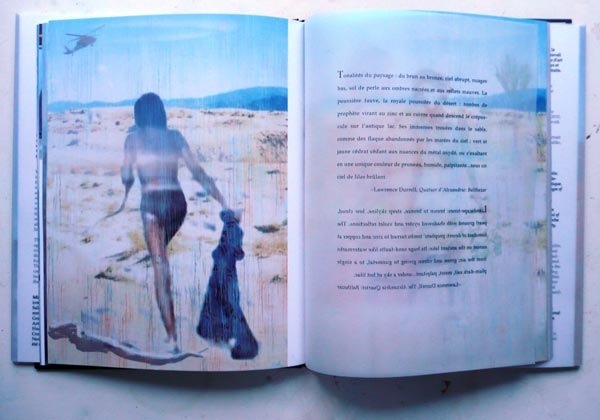

Marguerite Duras,Lawrence Durrell,

John Banville, Seamus Heaney and Vladimir Nabokov

Language: English / French

25.5 x 21.5 cm

5

4

2

1

7

6

16

15

18

17

9

8

10

9

12

11

28

27

30

29

32

31

37

36

39

38

49

48

7

6

9

8

5

4

PAINTINGS ON ARTISAN PAPER

Mia Funk is known for her intimate portraits of well-known figures, and of her friends and family. Her explorations and experimentations using oil paint, as well as her new works painted on antique handmade paper mounted on canvas, range from traditional to contemporary. I got to know Mia through my literary and arts journal, Her Royal Majesty. The following text is pieced together from a series of discussions we had in Paris during the summer of 2011.

Harriet Alida Lye: Though portraiture has existed essentially for as long as art has – in the Fertile Crescent, Egypt primarily, relics of portraits of gods and rulers proliferate – it was traditionally only used to memorialize the rich and powerful. Likeness mattered little. Now, portraiture is not only a genre, but an obligatory exercise for anyone who is training to become an artist. You focus almost exclusively on portraits and figurative work. Why?

Mia Funk: It’s always seemed the most interesting subject. It’s who we are. Portraits contain psychology, form, colour, it’s everything that we’re about and that interests us. I painted seascapes in the past, but it’s the human face, ultimately, that’s the most challenging, not only for painters, but for novelists, film makers. You don’t find many books or films about inanimate objects or landscape, there always has to be some human connection. A portrait should feel present, alive.

Harriet: For you, is that what makes a good portrait? That it should feel real?

Mia: Yes, a portrait should feel real.–That’s not to say it should be realistically painted, but real.

Harriet: It’s the same with writing...Being an editor is a little like curating, I read many submissions a year and choose only the ones that best tell the story or the theme for each issue. This goes for both text and visual work:

I have to feel drawn to the story, the characters, the scene. It seems to me the portrait artist is also a kind of storyteller, that they must go beyond the simple act of drawing a face in order to depict their subject. They are telling a story and must portray the personality and the history of the person.

Mia: Faces tell stories. They allow you to discover a person. There is nothing more satisfying in painting than looking at the face and building up its complexity line by line.

Harriet: When you are painting a portrait, where do you begin?

Mia: I always begin with the face. It’s is the most recognisable part of our anatomy, more than stance, height, or the way we walk.

"Faces tell stories.

They allow you

to discover a person."

Everyone has their own way of working, I start with the eyes because they’re the truth of the picture, you can get a lot of things wrong, but if the eyes are just a little too close together or far apart, your picture is ruined. Sometimes mouths are difficult, to find an expression that’s not contrived or frozen. There are so many things to get right when you’re painting faces, it’s the most challenging from the artist’s perspective.

Harriet: They say that an artist steals another's visage to represent his own. I find some of your portraits incredibly personal.

Mia: It’s difficult to avoid when you spend hours painting, something of you will always slip into the picture.

Harriet: I have been looking at your early paintings, the nudes and portraits of solitary figures and comparing it to what you are doing today. You’re always experimenting. Do you feel more comfortable in either? Or do you think you are still evolving as an artist, or have you found a single place you would like to evolve within?

Mia: I think I’m naturally restless, curious about things. I’ve never been the kind of person to settle in one place and spend all my life there. When I was growing up in America, I was already thinking about leaving. I looked around me and thought ‘is that all there is?’ I knew there were other ways of living, ways of seeing because my grandparents and their friends weren’t American.

I think it’s important to always remain curious, and so I’m a traveller in different styles...I think a lot of artists are restless or curious. I was never the kind of person who wanted to find one belle formule and to follow that path forever. Unfortunately a lot of artists can’t follow their curiosity on account of commercial constraints. I’ve been fortunate. Exhibiting in different countries allows me some freedom to follow different themes and when I feel I’m growing stale or want to try something new, I set a series aside and begin a new one. That way I can return to it when I feel like it, when my eyes are fresh.

It’s important for me to feel excited about what I’m painting, and I think that communicates itself to people when they see a painting, they can tell whether it was something an artist had to do, or if it was what she wanted to do. Also some of my series, like the audience paintings are incredibly demanding. I just completed one, a commission celebrating the Guinness Cork Jazz Festival. The painting features over twenty well-known jazz musicians, all of whom had to have a convincing likeness and be realistic as a whole, this group of people who were actually never assembled together. Paintings like that take a lot out of me, and then I have to retreat for awhile and do something else.

Harriet: Is that why you began your series of solitary portraits against motif backgrounds?

Mia: It was actually something I wanted to do for awhile and now seemed like a good time.

Harriet: Working on motifs and using patterns and artisanal paper, all this is something new for you. They are completely different from your audience paintings. Much more quiet.

Mia: It’s hard to paint quiet when you are painting crowds. The noise of a piece becomes visible, group portraits are like symphonies, you have to harmonise everything, and yet at the same time put across a single image, otherwise the painting won’t work. Whereas portraits of the individual sitter are like listening to a soloist.

Harriet: It’s interesting that you should mention music. I’m not usually aware of noise when I’m looking at a painting, but it’s true that pictures can make noise.

Mia: A lot of the expressions we use when talking about pictures come from music. It’s the first sense which we develop, although we’re not aware of it most of the time. In the womb, the first sound we hear is our mother’s heartbeat. When we discuss loud patterns or images we find striking, or talk about harmonious or clashing colours, we’re using terms we’ve borrowed from music. Expressionists aimed for a loudness and dissonance in their pictures, intentionally choosing colours that contrasted violently with each other, and that’s why it’s hard to look at some of them. Perhaps the most famous of expressionist pictures, Edvard Munch’s The Scream, aims at inducing that kind of reaction. But you are right, I was going for something quieter in these portraits.

Harriet: There is an evocation of inwardness. The lines are simple, but there’s a psychic depth that allows viewers to project themselves into the painting.

Mia: If they’ve achieved that, I’m happy. I began by looking for expressive motifs, patterns that would work like a visible underpainting. I liked the idea of working with the primary colours of childhood. I’d begin with a motif of roses or birds or paisleys or playing with the shape of an abacus, providing a lacework of external cues which evoke feeling and memory in the viewer.

Harriet: That’s what struck me about them. In particular Solace, which we reproduced in the latest issue of Her Royal Majesty. There’s this division between the inward condition, which is of course unrepresentable, and the outward being which can be seen and depicted but for that reason seems inessential. Your figures are deeply absorbed in what they are doing, thinking and feeling, so deeply the viewer is often made to feel that they are unaware of anything else. It reminds me of some of Picasso’s earlier work, actually. When he was still doing primarily figurative work. They also reminded me of some of your early paintings like The Letter and The Queen of Spades. Were you consciously returning to earlier themes?

Mia: In a way, I didn’t think about it, but I know what you mean. The paintings feel similar because they come from the same place.

Harriet: To me, they feel more personal.

Mia: Yes, anytime you’re painting a portrait of a famous person, viewers come to the painting with so many expectations. Everyone feels like they know the person already. And when you are working from photos or videos which I do, there is a layer of familiarity which is hard to escape. I would prefer to spend some time with the person, but sometimes this is not possible.

There’s this division between the inward condition and the outward being...her figures are deeply absorbed in what they are doing, thinking and feeling, so deeply the viewer is often made to feel that they are unaware of anything else.

Of course I always paint my own interpretation, I never use a single photo, but make a portrait from a combination of several different photos, so in that way it resembles a traditional sitting.

One photograph doesn’t give me enough information about what the person feels. I will paint eyes from one, the mouth from another, clothing from a video or dress them in a suit which they never wore. That way I feel the portrait is something I’ve created, it’s my own and it helps leap over the wall of familiarity.

My portraits of Francis Bacon came about like that, you will see him wearing suits and striking poses which you will never see elsewhere. Although he owned some suits, he was not usually photographed in them. More than most artists he was aware of the effect of the photographic image on one’s public persona and was photographed in his studio among the cans of paint, beside his table crusted with paint, and rarely in a suit. But in his own way Bacon was stylish, he designed sleek modern furniture before he became an artist and when he went out he always drank champagne, so he was bohemian, but he was also no slouch. And his paintings are stylish and bold and so I dressed him in a way that reflected that. An artist aware of himself, who made art to make a sensation...but I’m getting away from your question.

Harriet: We were talking about your use of motifs. Where did that come from?